After three years of research and restoration, Jan II Borman's iconic Saint George Altarpiece (1493) shines again in the Art & History Museum in Brussels. The interdisciplinary research, funded by the Jonckheere Fund, led to unexpected discoveries and provided answers to age-old mysteries.

Preserving an important heritage

The Saint George Altarpiece (1493) by Jan II Borman is a world-famous altarpiece and an emblematic work of the Museum of Art & History in Brussels. The René and Karin Jonckheere Fund, which aims to safeguard our cultural heritage and supports the conservation or restoration of works of art highlighting Brussels' European dimension, has therefore wholeheartedly financed the research and conservation treatment necessary to restore the altar to its former glory.

Unexpected discoveries came to light as well as an explanation of the mysteries that surrounded the altarpiece. The enlivened Saint George Altarpiece can be admired at the Museum of Art & History as of Saturday, April 24.

A spectacular altarpiece

The Saint George Altarpiece is one of the most beautifully carved wooden altarpieces in Western European history. It is spectacular in size and scope: no less than 5 metres wide and 1.60 metres high, with more than 80 meticulously detailed figures. It is the masterpiece of Jan II Borman, the greatest master of the Brussels artist dynasty of the same name, who was described as 'the best sculptor of his time'. He signed and dated the altarpiece in 1493.

The late Gothic scenes are world class. The lifelike characters are highly expressive and the carvings have an unparalleled virtuosity. In seven scenes, Borman illustrates the gruesome martyrdom of Saint George.

Interdisciplinary research and solved mysteries

This masterpiece of the Borman dynasty was thoroughly examined and then restored by the Royal Institute for Cultural Heritage. As the only signed work by Jan II Borman, for which a copy of the original written commission still exists, the Saint George Altarpiece is the key to understanding his creative genius.

Careful observation and laboratory analyses revealed that, contrary to tradition, the altarpiece had never been covered with polychrome. That also explains the remarkably fine carving of the wood.

The Greater Crossbowmen’s Guild of the city of Leuven is said to have ordered the Saint George Altarpiece for their chapel in order to gain favour with Maximilian of Austria, victor in the revolt of the Brabant and Flemish cities.

During the research, it was also revealed that the 19th-century restorer disassembled the scenes and put them back in a different order. This explains the mystery surrounding the bizarre order of the scenes. With the current restoration, the scenes are once again, after almost two centuries, in their original place.

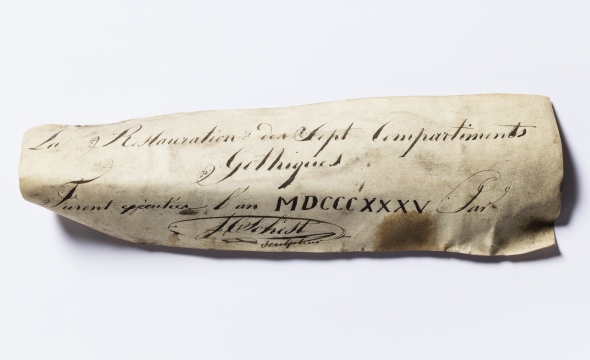

Secret hiding places

When disassembling the altarpiece and its wooden elements, one also found, in addition to loose fragments, a praying figure hidden under the sculpted scenes. Borman probably hid this ex-voto as a prayer or a gesture of gratitude. When the central scene was dismantled, the conservators also discovered a piece of parchment from the 19th-century restorer, stating that he treated the altarpiece in 1835. Both "discoveries" can be viewed at the museum over the next three weeks.

Does your (Brussels) museum or cultural institution also have a conservation or restoration project in the pipeline for a work of art highlighting Brussels' European dimension? If so, be sure to check out the René and Karin Jonckheere Fund's call for projects, which is launched annually around mid-January. Applications for the current call can be submitted until September 23, 2021.